“Scheherazade”

Chronicler of genocide

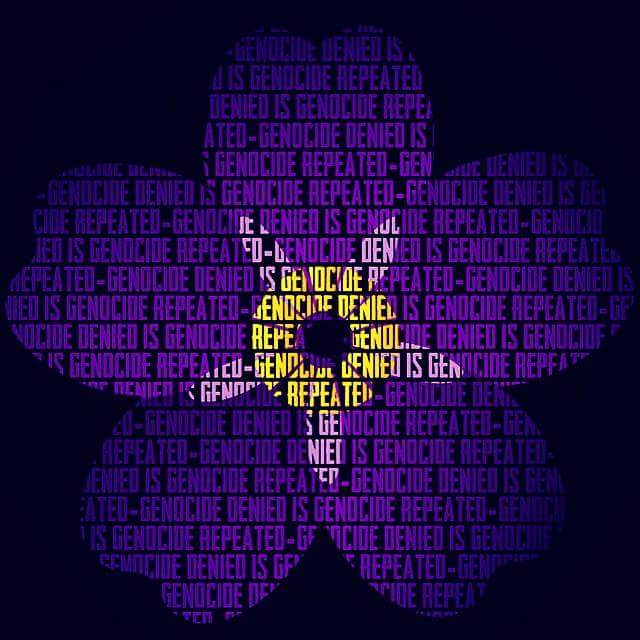

In memory of the 103 rd anniversary of the Armenian Genocide

I have read Franz Werfel’s epic work (900 pages) The Forty Days of Musa Dagh (1933), almost twenty years ago. A thrilling novel based on the appalling testimonies of Armenian refugees, whom the famous Austrian-Bohemian writer had encountered in Damascus, Syria in 1929, while touring the Middle East with his wife [i].

I was so much impressed by the events and the characters that for months they had become a part of me. I don’t know why, may be because I myself am a descendant of a genocide-survivor and my troubled soul has been haunted by countless stories of mass-killings and deportations.

To tell you the truth, I have sometimes asked myself the hypothetical question: Had Franz Werfel continued his journey in Syria traversing the concentration camps of Deir elZor to north-east Syria: Ras alAin, and my hometown Qamishli, he might have encountered, among countless other Armenian Genocide -survivors, my grandfather Bedros and heard his incredible story of death and resurrection! And why not? He might have produced his second masterpiece entitled Scheherazade, after the famous story-teller of the Arabian Nights!

It all started in a tiny village in south-east Turkey in the Batman province, Besiri district. A region predominantly inhabited by Kurds, some Armenians and other Christian minorities, during and in the aftermath of the Armenian Genocide perpetrated by the Ottoman-Turkey in 1915.

Following the horrible massacre of his extended family, the orphan Bedros, was not put to death for the sole reason of having been endowed with a wonderful voice and an amazing capacity of memorising and orally improvising Kurdish traditional songs of folk origin. Hence, the illiterate Armenian kid, who spoke only Kurdish, aged probably 14-15, would grow up to become the principal traditional-singer of an influential Kurdish feudal Chief in the region.

Each evening, the weary villagers and guests from the neighbouring areas flocked in the grand hall, presided by the Chief, eager to hear the “entertainment” of Bedros. He would recite from his endless “repertoire”, folk-songs and historic narratives he had heard since he was a little child: of ferocious battles, valiant heroes and great cities. He would also sing praises of the Chief, extolling his virtues as well as his ancestor’s merits! But not a word about the burning pain that was tormenting his body and soul: the gruesome images of the mass-killing of his family and the extermination of his entire race.

Like the intelligent heroine of the Arabian Nights who kept king Shahryar tantalized by her tales so that he would spare her life one more day, Grandfather never ever forgot his next day’s narrative, lest that would cost him his life.

But, while Schehrezade’s story finishes happily at the end of the One Thousand Nights, his ordeal takes yet another tragic turn.

One dreary late-night, having finished his “performance”, worn out and desperate, he drags his feet home at the extremity of the village to find a scene that would freeze his blood and leave him dumbfounded to the last day of his life! The house was totally plundered, his wife kidnapped and his little son and nephew both aged 3-4 years tightly tied to the window bars, throats slung from ear to ear…

Grandfather passed away few years following his miraculous escape to Syria after rescuing his wife. I did not see him, but remember well his pale face gazing out on emptiness from a photo hanging on the wall of our room. His wide-open eyes seemed desperately looking for someone to recount the untold narrative of his loved ones and many more other sad and heart-rending stories…

H. Dono

Membre de la rédaction vaudoise de Voix d’Exils

[i] – BBC radio documentary on Franz Werfel’s novel Forty Days of Musa Dagh http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b09pkmpc